Coding With Others Is Hard

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. And trust me, you’d code it worse without me!”

-Chad, a fellow coder

I’ve coded a decent amount of things in my life, and to be honest, it’s been fun. The freedom and the feeling you get when you code a program to do your bidding is addicting. It feels as if you’re a blacksmith, smelting the raw ore of standard libraries and algorithms and casting it into a mold of your design, to create a tool or weapon for the task at hand. And when you’re alone, you have complete freedom of the mold. But alas, we are all only human. We can’t do everything alone, we need company. So imagine my surprise when, as soon as I had this realization, an opportunity arose.

A commission

For the purposes of privacy, I’ll keep everyone’s name as secret as I can in this post. Last year, one of the teachers at my school approached me with a little project: an educational software for the school, in order for said teacher to use to quickly and efficiently administer tests to her students on computers at any time, anywhere. I agreed, under the pretense that I’d learn how to code something of this scale. That was more of a secondary reason, I wanted to procrastinate! Wahoo!

I dubbed the project VianuEdu in the idea that it would perhaps end up used by the whole school, not just the teacher mentioned before. You can find the source code for it here to follow along with my story. It’s written in Java, along with a server written in Go, which is entirely written by me. I picked Java because it was the quickest way to get a cross-platform GUI native program running without much of a hassle or making a website instead. I picked Go for the server because I wanted to try the language out with a nice server and make something new and exciting.

This is where the fun begins (ha)

Obviously, I realized a true educational software for the purposes that my teacher asked for was not something I could do alone, so I decided to take someone else along for the ride. Now the recruit very specifically asked I don’t mention his name in this post, so I’ll just call him Chad, even though he isn’t one.

Chad was a relatively passionate graphic designer, so I thought he would be fun to tag along to help with the client side of VianuEdu, which I was certain I’d screw up since I suck at designing UIs. He also had some experience coding Java GUIs (at least according to him) so I thought he’d be a good addition. It started off pretty well, he was eager to work, and I was excited to work together with others.

I started explaining to him the goals of the project, what he should do, started splitting our tasks, etc. and he agreed with most of what I gave him. I coded the backend (the server and the database handler) and he coded the frontend (UI and some small amounts of data handling). That was the plan. Soon, the plan instantly fell to pieces when I asked him:

“Hey, do you know Git?”

You know what he said?

“What’s Git?”

…

It is absolutely insane how many developers have worked on projects and have never used at least one type of version control. There is so many: Git, Subversion, Mercurial and all of them are immensely useful (the most used one is Git, though) and are critical for an easier developer workflow. Git’s branching features and the ability to maintain commit history is crucial for whenever a developer messes up and they will mess up. And then Chad asks what Git is.

I was wrong before, this is where the fun begins.

I soon came to the realization that Chad didn’t have an idea of what it meant to work with other people. In hindsight, I didn’t either, but I was at least willing to research the matter beforehand. I made a few notes, set up some foundations for ease of use, like Git and a style guide, and so on. But he just assumed we’d be fine.

In the end, I had to teach Chad everything he would have to know to properly code with others, now and in the future.

We started off nice and simple.

Git

Git is a free and open source distributed version control system designed to handle everything from small to very large projects with speed and efficiency.

Git is easy to learn and has a tiny footprint with lightning fast performance. It outclasses SCM tools like Subversion, CVS, Perforce, and ClearCase with features like cheap local branching, convenient staging areas, and multiple workflows.

That description might be very difficult to grasp. But the concept of Git is pretty simple.

Picture a text file you’re working on that contains a playlist you have on your phone. You can use Git to not only save the current version of the text file, you can use it to:

- experiment with different versions of the same playlist and never lose the original one

- review previous versions of the playlist

- work on two versions of the same playlist separately

- revert to a previous version of the playlist if the current one is bad or you accidentally deleted some songs

- do the same thing while more people work on the playlist

Git essentially holds in its special folder “.git” all the changes you make to files and keeps them in commits (a change to the project) and branches (different workspaces for the same project). Git is pretty damn important to work with in a multi-developer environment since it is the easiest way to manage lots of code without breaking any of the code you already have.

A very sweet tutorial for Git would be the one I used from Atlassian, and there is another pretty good one from GitHub, which you can find here.

Once I gave the same resources to Chad, he reluctantly ended up agreeing to use them, but even though Chad read most of the tutorials, he still didn’t use Git to its full advantage.

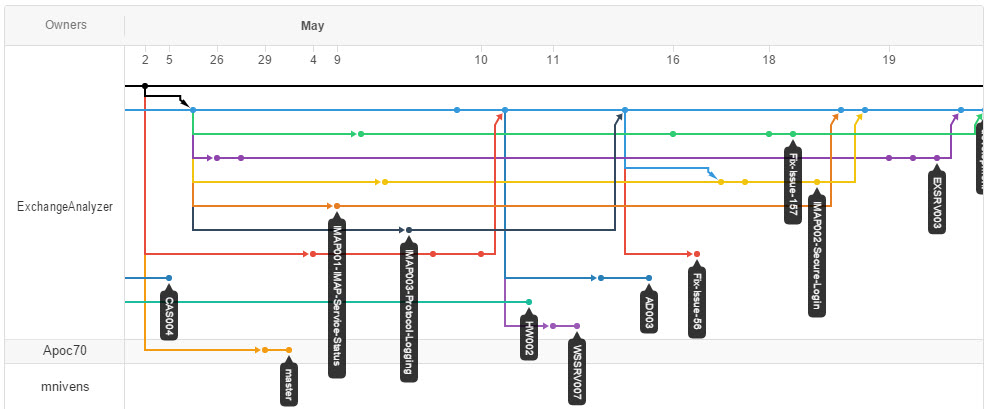

As you can tell, we eventually reached the point where branches were non-existent (notice the black “master” branch being the only one that appears towards the end) simply because Chad found it difficult to collaborate with me if we worked on different branches.

Alas, that was the least of my problems.

Documentation

By far the most important thing to do when working with others is to write documentation for your code. Documentation allows for you to not only clear your mind by explaining what your code does, but also help other coders, now or in the future, to understand your code. This is crucial when working with other fellow coders since you’ll be working on a lot of code, and it will be inevitable that you eventually forget what you did. Documentation refreshes your memory and makes it easier for you to see what a function does.

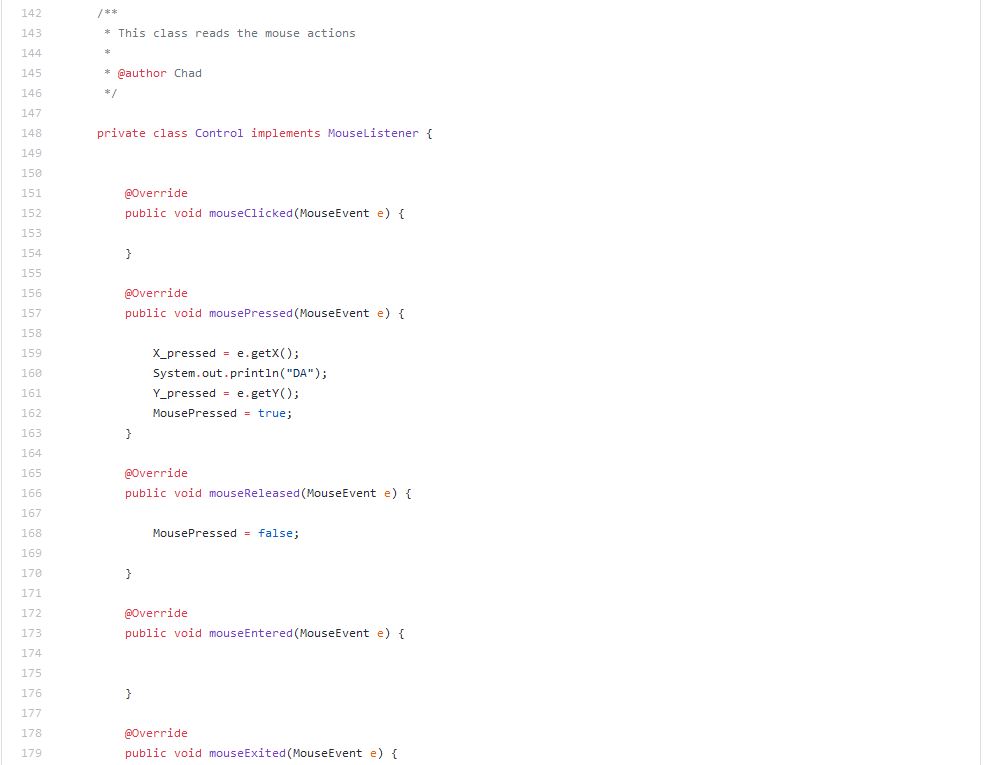

Many languages have different ways of dealing with documentation. Java, for instance, reads specific types of comments called JavaDoc comments and can automatically generate HTML pages of documentation for your project! VianuEdu’s JavaDoc can be found here.

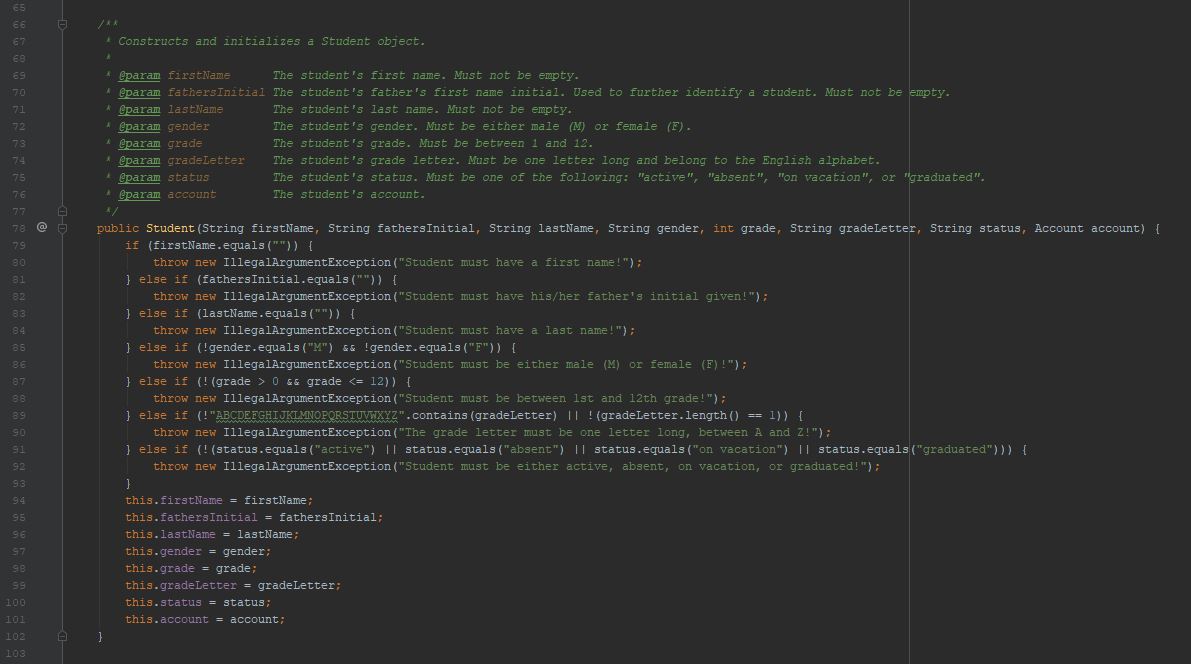

JavaDoc comments look something like this:

They contain information about the method (that’s a constructor), the parameters, and perhaps even more, such as exceptions, or some other stuff. A good JavaDoc comment allows for everyone to understand what a function does, and JavaDoc comments should accompany every method, every variable to help anyone else understand what is happening in the code they have in front of them.

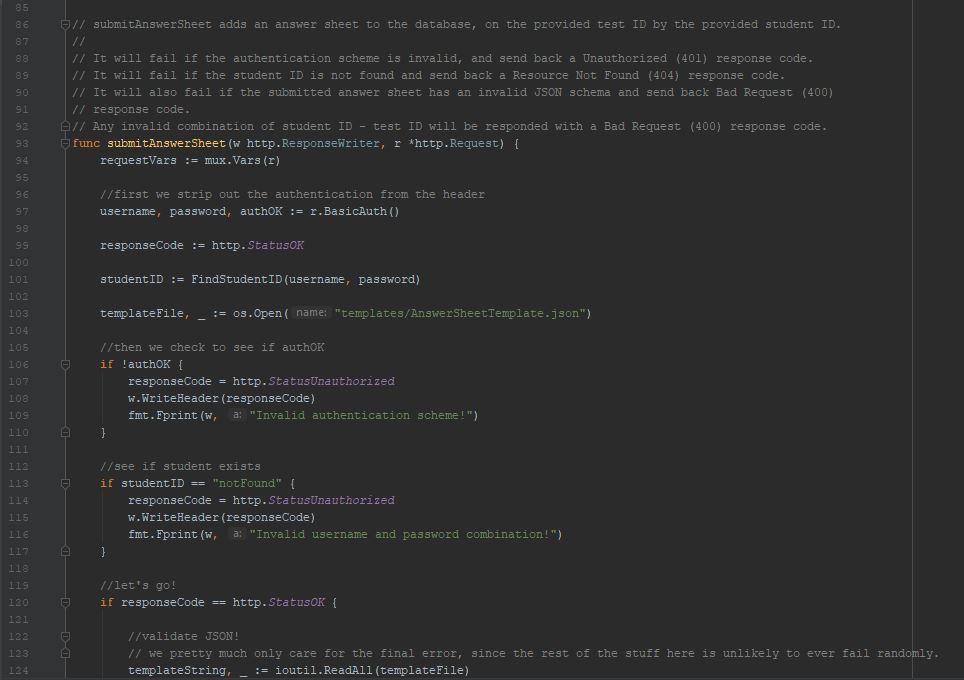

I like to think my code for the project was relatively well documented, what with every method having documentation, including internal ones, such as this one:

The Godoc comment at the top of the method allows for the Go toolchain to automatically generate documentation as well, much like JavaDoc does. You can find the generated documentation for the server of VianuEdu here. And as you can see, I thoroughly documented my code. In fact, I can assure you that all of it is documented, at least on the server side.

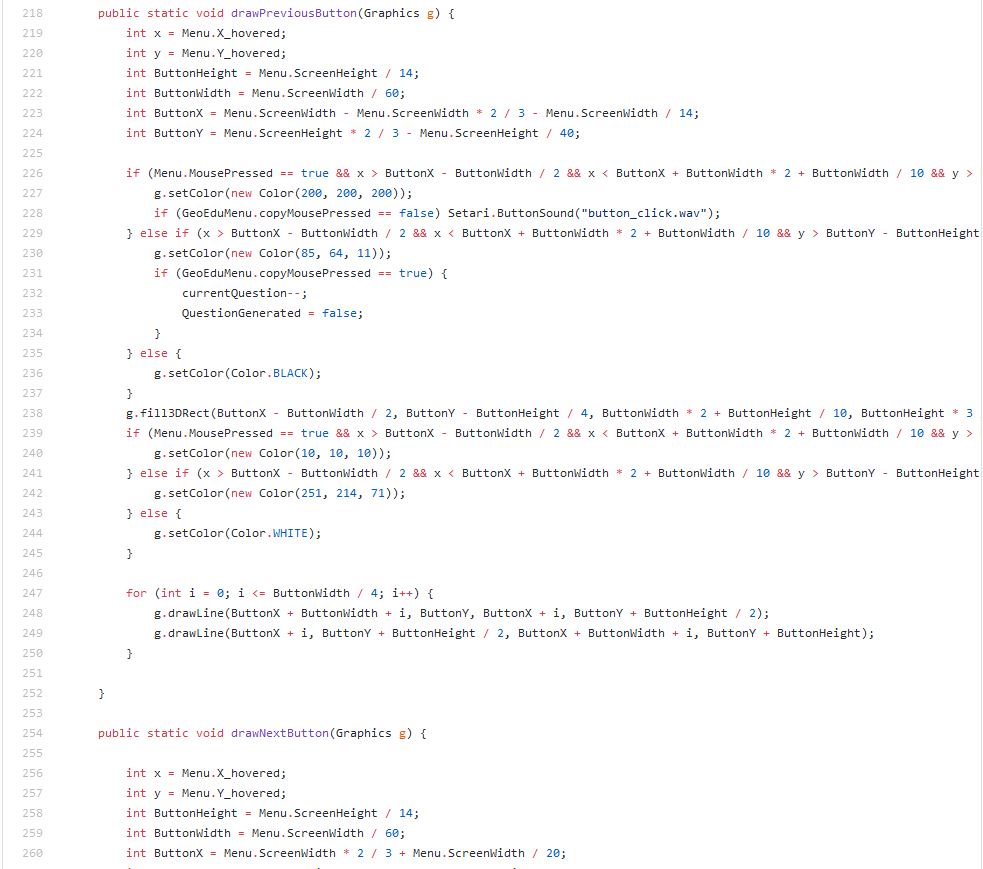

Compare that with fellow Chad’s code:

His code has almost no documentation at all. And if there is any documentation, it doesn’t really explain anything. It’s mostly just added there so that I can stop annoying him:

Yeah, no duh, I figured that out by myself, it’s literally in the method’s name!

Anyway, this has rendered Chad’s code unmaintainable, not only by me, but even by himself, since not even he remembers what he wrote in some sleepless night with 3 pots of coffee desperately chugged.

Of course, this wasn’t even the bad news’ final form!

Linter warnings

When I started the project, I urged Chad to use the IntelliJ IDEA IDE to work on our project. It’s a pretty damn good IDE that I wholly recommend you use when working on big Java projects. The reason why I urged him to use it is because it comes with an automatic linter built in with some relatively sane defaults. It makes sure your code is idiomatic and also comes with its own improvements to perhaps other perfectly fine code. It’s a good thing to have, especially when it brings up some awesome little improvements, like lambda replacements or even stream API linting:

This one in particular is straight from the IntelliJ website’s “What’s New” section.

Now I told Chad all about IntelliJ’s features and that he should use them. He said he would.

I was wrong to believe him.

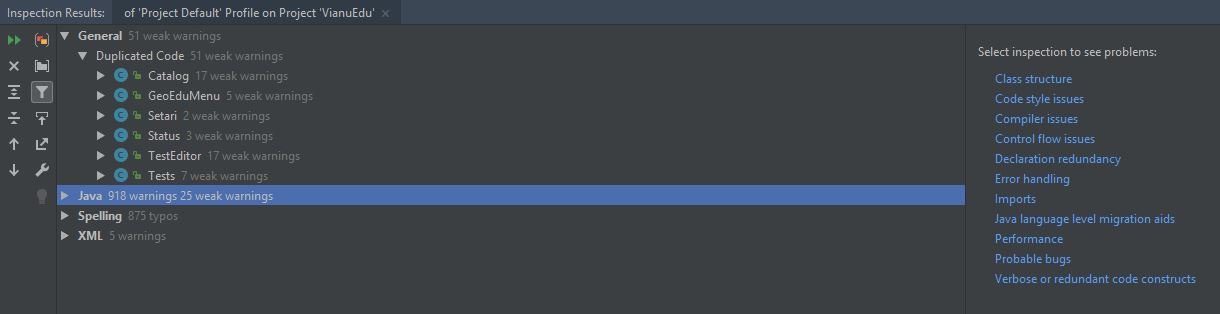

After about a month of work, I decided to check up on his side of the code and see what it looked like, see if he followed my advice:

He didn’t.

See that? That’s IntelliJ’s scroll bar. It shows you the warnings in yellow from the current file, for you to conveniently find and fix them. Chad’s scroll bar was completely yellow.

The grey parts of the scroll bar also shows you duplicate code, for you to refactor and put in a little function to call later. Literally 25% of one of his source files was duplicate code. Now that is an achievement. In total, Chad had 51 instances of duplicate code and 875 typos. Now the typos kind of don’t count, primarily because Romanian isn’t a default language for IntelliJ and also because Chad didn’t use camelCase variable naming, which is needed if you want IntelliJ to read typos right. However, none of that saves him.

He had 918 warnings, 55 of which were probable bugs, and 532 of which were declaration redundancies!

This is chaos.

This is chaos.

But wait! There’s more!

When I asked him to fix all the warnings as the final brush-up on our project, you know what he said?

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. And trust me, you’d code it worse without me!”

The End of the Journey

In the end, I finished my parts of the project and we released version 1.0 of VianuEdu. It was fine, it worked, albeit with a few GUI bugs we ironed out pretty quick (I wonder why there were any, Chad. Maybe the warnings were trying to tell you something). However, the experience taught me many things.

A lot of people are unaware of how to write clean code and also help others in the process of coding together with them. And you know why?

Because coding with others is hard.

When you’re alone, you can do whatever you want, no one judges you, you are free to write code in any way you like. But we are rarely truly alone when coding. You never know when you want someone new to join your project or when you have to join someone else’s project. You’d want to have the easiest time learning the new codebase, right? Well, that doesn’t happen just like that. You need to work in order to make your code accessible, easy to read, easy to refactor and modify.

I’ll admit that I did some wrongs in my project as well. We didn’t spend time training on using the IDE, I didn’t stay with Chad for a while to make sure he uses IntelliJ to the fullest extent, and I also didn’t take too much time to teach him Git, I just handed him some websites to read (much like I did with you), but the truth in the end is the same.

Learning to code with others is not easy, but it can be done. You have to:

- write clean code

- use proper version control

- have good documentation

- adhere to the project’s style guide

- have a common linter configuration to reduce warnings, errors and bugs

- communicate with your fellow coders

You need to make sure the code is uniform, cohesive, and easy for others to integrate as well. All of these things can be practiced but all it requires is the will to do so. Make everyone’s life easier when coding with others, lest you end up with an unmaintainable codebase. And who knows? Maybe the person you’ll be helping is you in the future, who will be a completely different person and end up hating your own code because you didn’t do it right.

I hope that you will at least learn from my experience and perhaps integrate some of these good practices in your code and development teams as well.